Mining

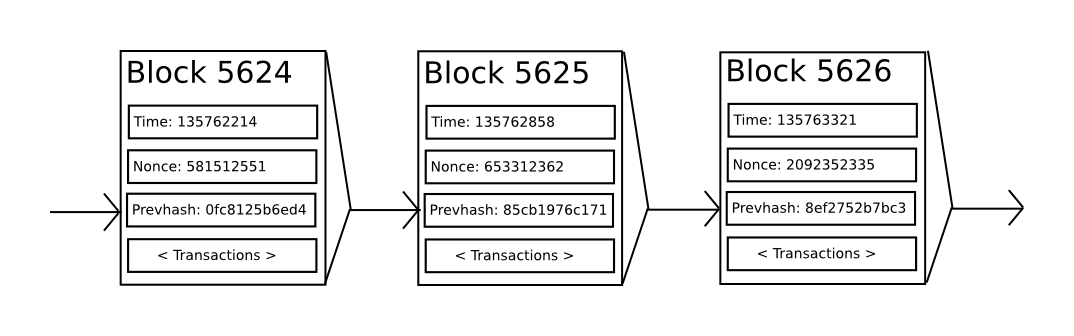

If we had access to a trustworthy centralized service, this system would be trivial to implement; it could be coded exactly as described, using a centralized server’s hard drive to keep track of the state. However, with Bitcoin we are trying to build a decentralized currency system, so we will need to combine the state transition system with a consensus system in order to ensure that everyone agrees on the order of transactions. Bitcoin’s decentralized consensus process requires nodes in the network to continuously attempt to produce packages of transactions called “blocks”. The network is intended to create one block approximately every ten minutes, with each block containing a timestamp, a nonce, a reference to (i.e., hash of) the previous block and a list of all of the transactions that have taken place since the previous block. Over time, this creates a persistent, ever-growing, “blockchain” that continually updates to represent the latest state of the Bitcoin ledger.

The algorithm for checking if a block is valid, expressed in this paradigm, is as follows:

- Check if the previous block referenced by the block exists and is valid.

- Check that the timestamp of the block is greater than that of the previous block[Note 2] and less than 2 hours into the future

- Check that the proof of work on the block is valid.

- Let

S[0]be the state at the end of the previous block. - Suppose

TXis the block’s transaction list withntransactions. For alliin0...n-1, setS[i+1] = APPLY(S[i],TX[i])If any application returns an error, exit and return false. - Return true, and register

S[n]as the state at the end of this block.

Essentially, each transaction in the block must provide a valid state transition from what was the canonical state before the transaction was executed to some new state. Note that the state is not encoded in the block in any way; it is purely an abstraction to be remembered by the validating node and can only be (securely) computed for any block by starting from the genesis state and sequentially applying every transaction in every block. Additionally, note that the order in which the miner includes transactions into the block matters; if there are two transactions A and B in a block such that B spends a UTXO created by A, then the block will be valid if A comes before B but not otherwise.

The one validity condition present in the above list that is not found in other systems is the requirement for “proof of work”. The precise condition is that the double-SHA256 hash[13] of every block, treated as a 256-bit number, must be less than a dynamically adjusted target, which as of the time of this writing is approximately 2187. The purpose of this is to make block creation computationally “hard”, thereby preventing Sybil attackers[12] from remaking the entire blockchain in their favor. Because SHA256 is designed to be a completely unpredictable pseudorandom function, the only way to create a valid block is simply trial and error, repeatedly incrementing the nonce and seeing if the new hash matches.

At the time of writing, for a target of ~2187, the network must make an average of ~269 tries before a valid block is found; in general, the target is recalibrated by the network every 2016 blocks so that on average a new block is produced by some node in the network every ten minutes. In order to compensate miners for this computational work, the miner of every block is entitled to include a transaction giving themselves 12.5 BTC out of nowhere. Additionally, if any transaction has a higher total denomination in its inputs than in its outputs, the difference also goes to the miner as a “transaction fee”. Incidentally, this is also the only mechanism by which BTC are issued; the genesis state contained no coins at all.

In order to better understand the purpose of mining, let us examine what happens in the event of a malicious attacker. Since Bitcoin’s underlying cryptography is known to be secure, the attacker will target the one part of the Bitcoin system that is not protected by cryptography directly: the order of transactions. The attacker’s strategy is simple:

- Send 100 BTC to a merchant in exchange for some product (preferably a rapid-delivery digital good).

- Wait for the delivery of the product.

- Produce another transaction sending the same 100 BTC to himself.

- Try to convince the network that his transaction to himself was the one that came first.

Once step (1) has taken place, after a few minutes some miner will include the transaction in a block, say block number 270,000. After about one hour, five more blocks will have been added to the chain after that block, with each of those blocks indirectly pointing to the transaction and thus “confirming” it. At this point, the merchant will accept the payment as finalized and deliver the product; since we are assuming this is a digital good, delivery is instant. Now, the attacker creates another transaction sending the 100 BTC to himself. If the attacker simply releases it into the wild, the transaction will not be processed; miners will attempt to run APPLY(S,TX) and notice that TX consumes a UTXO which is no longer in the state. So instead, the attacker creates a “fork” of the bitcoin blockchain, starting by mining another version of block 270,000 pointing to the same block 269,999 as a parent but with the new transaction in place of the old one. Because the block data is different, this requires redoing the proof of work for the concerned block. Furthermore, the attacker’s new version of block 270,000 has a different hash, so the original blocks 270,001 to 270,005 do not “point” to it; thus, the original chain and the attacker’s new chain are completely separate. The rule is that in a fork the longest blockchain is taken to be the truth, and so legitimate miners will work on the 270005 chain while the attacker alone is working on the 270,000 chain. In order for the attacker to make his blockchain the longest, he would need to have more computational power than the rest of the network combined in order to catch up (hence, “51% attack”). Bitcoin blocks depend on the hash of all previous blocks. An attacker with immense computing power can redo the proof of work (PoW) for a considerate amount of blocks and can eventually gain a lot of bitcoins but as described in Satoshi’s paper,[1a] the reward to mine a valid block is much more than to disrupt the network. But in light of falling mining rewards the same does not hold true.